Lot #692 - John Heaviside Clark

-

Auction House:Mossgreen

-

Sale Name:The Denis Joachim Collection

-

Sale Date:19 Jun 2016 ~ 2pm - Session 1: Lots 1 - 321

20 Jun 2016 ~ 10am - Session 2: Lots 322 - 480

20 Jun 2016 ~ 2pm - Session 3: Lot 481 - 688

20 Jun 2016 ~ 6pm - Session 4: Lots 689 - 818 -

Lot #:692

-

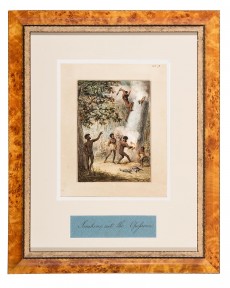

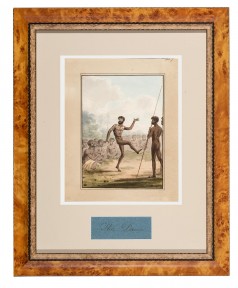

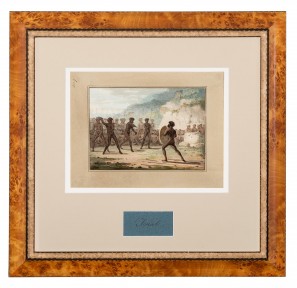

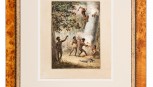

Lot Description:John Heaviside Clark

(circa 1770-1863)

(Field Sports of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales) Circa 1813

watercolour over underdrawing in pencil

(i) New South Wales: Smoking out the Opossum, inscribed top right on margin: No 3, 18.7 x 13.5 cm (image); (ii) Fishing [I], inscribed top right on margin: 61, 13.3 x 18.7 cm (image); (iii) Hunting the Kangaroo, inscribed top left on margin: No 4; inscribed top right on margin: 58, 13.4 x 18.6 cm (image); (iv) Throwing the Spear, inscribed top left on margin: No 1; inscribed top right on margin: 59, 13.3 x 18.7 cm (image); (v) Climbing Trees, inscribed top right on margin: No 2, 18.7 x 13.3 cm (image); (vi) Fishing [II], inscribed top right on margin: No 6; and: 62, 13.4 x 18.2 cm (image); (vii) The Dance, inscribed top right on margin: No 7, Watermarked: J WHATMAN1/ [possibly 1808? Partially legible], 18.8 x 13.2 cm (image); (viii) Warriors, inscribed top left on margin: No 8, 13.3 x 18.6 cm (image); (ix) Trial, inscribed top left on margin: No 9, 13.3 x 18.5 cm (image); (x) The Repose, inscribed top left on margin: No 10, 13.4 x 18.6 cm (image) -

Provenance:Topographical Paintings, Drawings and Watercolours, Sotheby’s, London, 4 November 1987, lots 97–106 (illustrated); Dallhold Investments Collection, Perth; Fine Australian Paintings, Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 19 April 1993, lot 347 (illustrated)

-

Exhibited:Australian Images: prints, drawings and watercolours from the collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 22 December 1979 – 28 January 1980; Paradise Possessed: the Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 6 August 1998 – 7 February 1999; Eora: mapping Aboriginal Sydney, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 5 June – 13 August 2006, cat. no. 16 (Trial)

-

Notes:LITERATURE (THE ENGRAVINGS): John Heaviside Clark, Field Sports &c. &c. of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales, Edward Orme, London, 1813 [?] (illustrated); John Heaviside Clark, Foreign Field Sports, Fisheries, Sporting Anecdotes, &c. &c., Edward Orme, 1814, [re-issue of 1813 [?] edition as Supplement], pp. 157-170 (illustrated); Tableaux des chasses le plus intéressantes: représentées en gravures coloriées, pouvant servir d'études de lavis et d'aquarelle, chez A. Nepveu, Librarie, Paris, 1819 (illustrated, Hunting the Kangaroo, Throwing the Spear, and Climbing Trees); Rex and Thea Rienits, Early Artists of Australia, Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1963, pp. 196-7; Jane de Teliga, Australian images: prints, drawings and watercolours from the collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1979; Tim Bonyhady, Images in Opposition, Oxford University Press, Melbourne 1985, p. 26; Jonathan Wantrup, Australian Rare Books, Horden House, Sydney 1987, pp. 280-283; Jeannette Hoorn, The Lycett Album: drawings of Aborigines and Australian scenery, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1990, pp. 3, 17, 25 (illustrated, Throwing the Spear, and Trial); Perceval Painting fetches $143,000’, in Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 20 April 1993, p. 6; Country Life, Sotheby’s: topographical paintings and 18th and 19th century British drawings and watercolours, London, 1987 [advertisement], p. 59 (illustrated, Hunting the Kangaroo); Paradise Possessed: the Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1998, p. 75; Diana de Bussy, The Alan Bond Collection of Art, Dallhold Investments Pty Limited, 1990, pp. 22-29 (illustrated); Elizabeth Lawson, Birds! A National Library of Australia Exhibition, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1999, pp.4 (illustrated, Throwing the Spear), 9; John Robert Thompson, Collections in the National Library of Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2003, pp. 20 (illustrated, Smoking Out of the Opossum), 75; Eora: mapping Aboriginal Sydney, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 5 June – 13 August 2006, p.16 (illustrated, Trial); Julien Renard, Aboriginal Life in Old Australia, Edition Renard, Melbourne 2003 (illustrated); Kirsty Grant, On Paper: Australian prints and drawings in the National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 22-3 (illustrated, The Dance, and Climbing Trees); Val Attenbrow, Sydney’s Aboriginal Past: investigating the archaeological and historical records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, (illustrated cover, Smoking out the Opossum) "1. James Whatman paper has also been known to be used in the publication of Field Sports […]" NOTES: John Heaviside Clark remains a mysterious figure, which is somewhat surprising as both contemporary and posthumous accounts indicate he lived a long and productive life in Britain, playing an active role in the promotion, publication and instruction of painting and printmaking. Historians are not even certain of his year and place of birth, though sometime around 1770, somewhere in Scotland, seems to be the generally agreed approximation.1 He was indeed an artist of modest repute – best remembered in England for his heroic part in recording the immediate aftermath of the slaughters of Waterloo, earning him the appellation ‘Waterloo Clark’.2 He was by no means a revolutionary artist though, never drifting too far from the academic manner of the Picturesque and the Romantic that so ubiquitously defined his times. It would be fair to say that his art remains of greater interest for its subject matter than for its style or technique. A frequent exhibitor at the Royal Academy from 1801 to 18333, he became popular in the 1820s as a maker of the modern portable diorama, an example of which exists in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.4 His ability as an educator was exemplified in a number of illustrated publications he authored, including A Practical Essay on the Art of Colouring and Painting Landscape – a sort of ‘paint by numbers’ how-to guide, which actually enjoyed several reprints and editions. Clark’s connection with the New South Wales Colony begins in 1810 in London when he produces four aquatints after watercolours of Views of Old Sydney, by John Eyre (State Library of New South Wales, Sydney).5 It is Clark’s 1813-14 publication of Field Sports &c, &c, of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales, however, that makes him an important, yet puzzling figure for early Colonial art and Aboriginal studies. Field Sports […] was published by Edward Orme of London as a plate book of ten coloured engravings (executed by Matthew Dubourg) after the present watercolours, which are attributed to Clark, who was also the assumed author of text that accompanied the images. The book explains and illustrates the customs, rituals, manners, habits, and current state of affairs of New South Wales’ Aborigines, albeit in that typical tone of settler superiority which defined much of the early literature on indigenous culture. Although it’s an account from this bias perspective of a free Colonist, skewed by a general prejudiced misunderstanding of the native culture, the detailed descriptions remain important to our anthropological understanding the indigenous civilisation of the area. Furthermore, Field Sports […] was the first book solely devoted to the Aboriginal people as its subject, making it a seminal work for this area of study.6 The underlying enigma that arises, however, is that John Heaviside Clark never set foot in Australia – a rather unusual distinction for someone who wrote and painted with such authority on the subject; (this is not the only instance in which Clark was credited with “del”, or the one after who the etching is done. Other examples include South American Catching a Bull, 1813; and Torchlight Fishing in North America, 1813). It is now widely accepted that these watercolours by Clark must have been mined from some other, now lost, source.7 However, they remain some of the most important records of early colonial times still in private hands today. For decades now, scholars have pondered which of Clark’s contemporaries may have ‘provided’ him with the material. Among the potential artists is the draughtsman and naval officer, Joseph Swabey Tetley (circa 1778–1828) who spent a brief six months in the Colony.8 However, the style and character, or caricature rather, which distinguishes Tetley’s comparable works, most notably ‘Natives of New South Wales, drawn from life in Botany Bay’ (State Library of New South Wales, Sydney), is too far removed in sentiment from the distinctly more elegant and dignified figures in the present images. Elsewhere, it has been suggested that the imagery was ‘possibly’ or ‘probably’ (depending on which source one consults) derived from John William Lewin (1770-1819), Australia’s first free professional artist.9 Lewin is recorded to have produced a series of Aboriginal studies of which no visual trace remains. The hypothesis suggests that Clark’s images are transcriptions of Lewin’s work.10 This idea now seems to be slowly fading from textbooks. Indeed, it is difficult to believe that the anatomically crooked and dog-like kangaroos in Hunting Kangaroos from Field Sports […] could be related to the same hand that drew the 1819 Kangaroos in a Landscape (John William Lewin, National Library of Australia, Canberra). By 1813, Lewin was already an accomplished natural-history painter with a keen eye; he had been in Australia long enough to know the shape and form of a kangaroo, thus, unlikely to have painted such strangely misshapen representations of the animal. Another more recent attribution, suggested by Julien Renard, is that the images are ameliorated adaptations of sketches executed by Rear Admiral William Bligh (1754-1817), to whom Clark’s book is dedicated.11 But there are no stylistic grounds on which to base this idea, and as Renard notes, ‘Bligh was not known to have had a particular interest in the Australian Aborigines.’12 Finally, there is one more draughtsman worth considering – that of Philip Gidley King (1758-1808). Unlike Bligh (who succeeded King as Governor of the Colony in 1806), King had an inquiring mind toward the practices of the Aboriginal people of Australia. This is most eloquently displayed in the five simple, yet striking watercolours attributed to King and held in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales.13 The two bodies of work, that of Clark and King, clearly share common themes which include fishing in canoes, figure studies in active poses, and families in idle respite. Furthermore, and of greater significance, is the strikingly similar style and tone in both. Although King’s sketches are distinguished by a greater degree of naive directness and simplicity in design, a comparative analysis between the present works and those by King raise the possibility of a shared source. This is best demonstrated when comparing Clark’s Dance with King’s Watercolour of an Aboriginal Man circa 1790. The confident figures in defiant stances, with all their muscular charm, clear profiles, and detailed curls in their hair, are treated with equal nobility and grace. In the various postures and poses used by both artists there are distinct quotes of Classical statuary: while King’s Watercolour Illustration of Man Carrying a Spear is an echo of the Roman sculpture of Marcellus (Musée du Louvre, Paris), we see a similar pedigree in Clark’s The Repose where the figure on the right is clearly a citation of the Classical Doryphoros.14 If King provided the blueprints, as it were, it is yet unclear how or when they got to London. Although King arrived in Norfolk Island in 1788, he did return to London on three occasions. First, in 1790 to report on the settlement; he was there a second time on prolonged sick leave between 1797 and 1799, and finally bas back in the English capital in 1807, dying there within a year. One of King’s watercolours at least, A Family of New South Wales (circa 1790), was known in London through its engraving by William Blake. While it remains unclear whether the present watercolours were copied, interpreted, or simply appropriated by Clark, their significance to Australia’s history, art, and culture remains indisputably immense. Although at the time of their production there was hardly an Australian market for such imagery, they, and the engravings which followed, served to satisfy England’s insatiable appetite for records and relics of its distant Colony. Indeed, there was a strong market for anything concerning the curious fauna and exotic flora of the Pacific, and Clark’s Field Sports […] fulfilled this demand, even benefiting from a partial reprint in French in 1819.15 The interest and hype around the ‘foreign’, the ‘romantic’ and the ‘distant’ remained strong in Europe throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But slowly, if belatedly, Australia began to realise, appreciate and value its own early heritage. Early and important images such as the present works came out of London and were brought back to Australian shores. These ten watercolours are remarkable for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is their early date (probably around 1813). Secondly, they played a seminal role as documentary records of early indigenous cultures. Thirdly, they are in their own right aesthetically delightful works of art. Then there is their exceptionally excellent condition. And finally, they have happily remained together as a complete set for over two hundred years. This combination of attributes is rare and surely raises them to the status of a ‘national treasure’. It is anticipated then, as it is necessary, that they enter into an equally significant and deserving collection. Petrit Abazi 1 Michael Bryan, Dictionary of Painters and Engravers: biographical and critical, George Bell and Sons, London, 1886, p. 280; 2 Ibid; 3 See Charles Lane, Sporting Aquatints and their Engraver: 1775-1820, Leigh-on-Sea, pp.51-3; 4 Accession number 32.83.3(1-2); see also Vanessa Toulmin Simon Popple, Visual Delights Two: exhibition and reception, John Libbey Eurotext, London, 2005, pp. 187-8 ; 5 See Michelle Hetherington, Seona Doherty, The World Upside Down: Australia 1788-1830, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2000, pp. 30-1; 6 See John Robert Thompson, Collections in the National Library of Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2003, p. 20; and Julien Renard, Aboriginal Life in Old Australia, Edition Renard, Melbourne 2003; 7 For the purposes of this brief analysis, we will leave the text to one side and focus the imagery; 8 See Joan Kerr (ed.), The Dictionary of Australian Artists: painters, sketchers, photographers and engravers to 1870, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992, p. 788; 9 See Ibid.; see also Rex and Thea Rienits, Early Artists of Australia, Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1963, p. 197; see also Jonathan Wantrup, Australian Rare Books, Horden House, Sydney 1987, pp. 280-283; see also Elizabeth Lawson, Birds! A National Library of Australia Exhibition, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1999, p. 4; see also John Robert Thompson, Collections in the National Library of Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2003, p. 20; 10 See Rientis, p. 197; 11 Julien Renard, Aboriginal Life in Old Australia, Edition Renard, Melbourne 2003, p.53 [not paginated]; 12 Ibid., p. 55 [not paginated]; 13 Produced circa 1790, Brabourne Collection, Bank Papers, Series 36a; 14 This particular image would have been known through plates in Le Antichità di Ercolano, known to have been circulated in London since 1773. ; 15 Only three plates (Hunting the Kangaroo, Throwing the Spear, and Climbing Trees) were used in not only altered title and format, but also with substantially altered backgrounds, See Tableaux des chasses le plus intéressantes: représentées en gravures coloriées, pouvant servir ‘études de lavis et d’aquarelle, chez A. Nepveu, Librarie, Paris, 1819. ESTIMATE ON REQUEST

-

Estimate:A$0 - 0

-

Realised Price:

-

Category:Art

This Sale has been held and this item is no longer available. Details are provided for information purposes only.