Lot #12 - Leonard French

-

Auction House:Mossgreen

-

Sale Name:Fine Australian & International Art

-

Sale Date:06 Jun 2017 ~ 6.30pm

-

Lot #:12

-

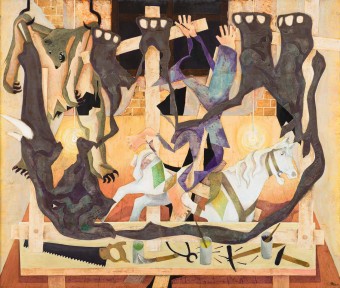

Lot Description:Leonard French

(1928-2017)

The Workshop

oil on board

152 x 181 cm

signed lower right: French -

Provenance:Collection of the artist; Adrian Slinger Galleries, Brisbane; Private collection, Queensland (purchased from the above in 1989)

-

Exhibited:Leonard French: dream images from childhood people, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 1-13 November 1982, cat 3

-

References:Leonard French, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 1982, exhibition catalogue, (unpaged); Judy Newman, ‘Broken images an expression of lonely youth’, The Australian, 4 November 1982 , (unpaginated press clipping, cited NGV artists file), (the series); Sandra McGrath, ‘French unveils his sinister circus’, in The Australian, 15 August 1981, (unpaginated press clipping, cited State Library of Victoria, AAA file), (for the series)

-

Notes:When examining the life and work of the late Leonard French, one frequently stumbles upon the uncanny affinities, however coincidental or apparently trivial, shared between French and the great Renaissance master, Michelangelo. Although separated by centuries of stylistic and social developments, the parallels, in fact, underscore how the characters of some great artists can transcend time and space. Whether or not French was aware of it, there is a incessant sense that he was a new-age Michelangelo. The first shared experience is detected in the early childhood environments of each artist. Michelangelo, following the premature death of his mother, was raised by a nanny, whose husband was a stonemason. The young Michelangelo attributed to this relationship, and the access it gave to marble quarries, ‘a knack of handling chisel and hammer, with which I make my figures’1. Masonry, albeit of a less noble kind, was an important element in French’s childhood. His father worked at the Brunswick Brickworks (now redeveloped into trendy hipster apartments), which the young French frequented at an early age. Although masonry would not find the same practical application as marble had with Michelangelo, French identified the origins of the ordered, geometric grid-like brickwork patterns, which appear throughout his oeuvre – including the present work – to these early excursions.2 Secondly, both artists were ostensibly self-taught – and proudly so. Michelangelo’s assertion that he was an auto-didact was so strong that no biographer dared declare in print that he may have, in fact, been an apprentice, at the age of fourteen, in the studio of Ghirlandaio. Vasari, not wanting to offend Il Divino, did not publish his second edition of Le Vite, confirming the Ghirlandaio connection, until Michelangelo had died.3 At fourteen, French left formal secondary school education, becoming a sign-writer, then progressing from stylising calligraphic signs to painting iconographic symbols. French also took pride in his self-made talent. ‘All painters don’t come out of art schools’, he declared contemptuously, ’I don’t see any value in art schools – an utter waste of time!’.4 Then, there are the religious and mythological themes characterise the many private and public works of both artists. Michelangelo had little choice, having been born in a time when most commissions derived from the Church or devout patrons. However, in mid-twentieth century Melbourne – an era distinguished by growing secularisation – religious art had become increasingly démodé. In the 1950s and 1960s, abstract expressionism and minimalism were taking hold of local artists. With increasing self-referential and real-world substance making it onto canvas, only few found the space for divine manifestations. It was during this shift that, and perhaps as an antidote to it, in 1951, the Blake Prize for religious art was founded. French won the award twice. Despite this, French was not a remarkably fervent Christian. Although considered to be a deeply spiritual man, he never declared any great religious conviction. Similarly, Michelangelo was probably more spiritual than religious. In a vindictive letter which he received from the Italian poet, Pietro Aretino, he is denounced as a ‘Christian… [who] rates art higher than the faith’5. Nevertheless, through his talented draughtsmanship, great sense of design, dramatic bravura and intricate compositions, he delivered the most memorable art in Christian history. French, in the Australian context, also delivered notable religious works. One of his largest commissions was a modern seven-panel polyptych representing Genesis: the seven days of creation, (Australian National University, Canberra). It may not hold the same conversionary power felt in Michelangelo’s paintings of the same subject, yet the ensemble remains as an important essay in how spiritual revelations could be eloquently manifested through symbolic and abstract representation. Fourthly, and perhaps the clearest parallel to be drawn from the lives and works of Michelangelo and French lays in their ambitious ceiling works – they are among the most monumental in Western art history. The frescoes of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, and the stained-glass Great Hall, in Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria, are their undisputed masterpieces. They laboured four and five years, respectively, to complete the herculean tasks; projects which, in some way, broke them both: physically, in the case of Michelangelo, and figuratively in French’s – the unveiling of the NGV ceiling marked, at once, French’s career highlight and the beginning of a steady decline in recognition, attention and critical relevance. Ironically, both their masterpieces were created in mediums that were not their favoured. Michelangelo, after all, was a sculptor; French, never worked on a stained-glass project again. Nevertheless, every year, millions of visitors turn their gaze heavenwards to take in the visual spectacle and give in to their transcendental lure. As they matured, both artists became increasingly, and exceptionally, private individuals. Michelangelo’s apprentice and biographer, Asciano Condivi, described the greying artist as ‘bizzaro e fantastico’, who increasingly, ‘withdrew himself from the company of men’.6 Although French is not commonly described as bizarre fantastical by nature, his choice to leave Melbourne and relocate his studio to Country Victoria, and thus turn his back on the art world, was an eccentric move. However, his removal from art politics and decision to not show regularly (not wanting to be dictated by the demands of the art market) did not thwart his work ethic. He only exhibited his paintings when he had a body of work that he was entirely happy with. The present, large-scale painting, The Workshop, (circa 1980-2) was produced following a period of reflection, remembrance and reconciliation. It is an ichnographically rich work - a synthesis of quotidian experiences, childhood memories, art-historical quotations and biblical citations. As the title suggests, we are probably in the studio of the artist. In the foreground, we see open cans of paint – French, like the old masters, always mixed his own pigments rather than squeezing paint from tubes. Hanging and hovering in the centre of the work are various circus animals and a ‘fragmented rocking horse; a flattened cardboard like image like a stage prop, which had its origins in recollections of a merry-go-round, French rode as a boy.’7 As well as these autobiographical sources, there is more than a hint of Picasso’s Guernica, only here, the circus of war is replaced with that of less bellicose nature. The biblical references are evident in the nails and hammer that sit on the altar-like mensa. The tools of carpentry are perhaps another religious reference to the early trade of Jesus Christ. The crucified hand, a further, and final, allegorical citation. Could this be hanging figure, which is only partially legible, be the body of the artist, one who has devoted his life and work to the production of art? If so, it is difficult not to recall Michelangelo’s self-portrait as a flayed, lifeless soul, one that had been squeezed to the last drop in the name of art, in his epic Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. In January 2017, in his eighty-eighth year – the same age Michelangelo was when he died (marking the final, solemn, link between the two artists) – French passed away. He had dedicated his whole life towards creating lasting images of transformative power. Having been largely neglected for many years, there has never been a better time to revisit and to art-historically canonise the eremite master. Petrit Abazi 1 Charles de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1969, p. 11; 2 See Judy Newman, ‘Broken images an expression of lonely youth’, The Australian, 4 November 1982; 3 See Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite dei piu eccelenti pittori, scultori e atchitetti, Newton Compton, Rome, 2007, p.1202-3; 4 Cited in Sasha Grishin, ‘Leonard French’, in Oz Arts (online version), www.ozarts.net.au/images/oz-arts/2017-winter/leonard-french.pdf; 5 Sidney Alexander, Nicodemus: the Roman years of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ohio University Press, Ohio, 1984, p. 110 ; 6 Asciano Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, translated second edition, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999, p. 106; 7 Judy Newman, ‘Broken images an expression of lonely youth’, The Australian, 4 November 1982 (unpaginated press clipping, cited NGV artists file)

-

Estimate:A$45,000 - 65,000

-

Realised Price:

-

Category:Art

This Sale has been held and this item is no longer available. Details are provided for information purposes only.