Lot #72 - Stephen Bush

-

Auction House:Deutscher and Hackett

-

Sale Name:Important Australian & International Art

-

Sale Date:28 Aug 2013 ~ 7pm

-

Lot #:72

-

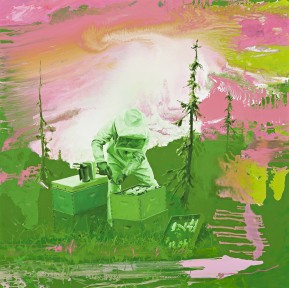

Lot Description:Stephen Bush

1955

Vert De Sevres, 2004

oil and enamel on linen

183.0 x 183.0 cm

signed and dated three times verso: Stephen Bush 2004 inscribed verso: Vert de sevressigned and dated three times verso: Stephen Bush 2004 inscribed verso: Vert de sevressigned and dated three times verso: Stephen Bush 2004 inscribed verso: Vert de sevres -

Provenance:The John L. Stewart Collection, New York, purchased directly from the artist, c2004

-

Exhibited:Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 10 February – 13 May 2007Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 10 February – 13 May 2007Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 10 February – 13 May 2007Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 10 February – 13 May 2007Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 10 February – 13 May 2007Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 10 February – 13 May 2007St

-

Notes:The caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMANThe caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMANThe caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMANThe caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMANThe caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMANThe caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMANThe caretaker is perhaps the most powerful and encumbered character in Bush’s repertoire. His earliest appearance is in Bush’s 1988/1989 Caretaker series (lots 73 – 76) in which he dons a garishly gold full-body suit, a call-back to Elvis Presley’s gold suit from his 1968 comeback tour.1 But the caretaker is rife with more symbolic significance than this one peculiar cultural allusion. The same character reappears later in Bush’s 2004 works Swamp Gum and Vert de Sevres, this time subsumed within great swells of psychedelic colour. The caretaker’s costume also calls to mind a beekeeper suit, and in this way the character evokes Bush’s earlier themes of conquest, capture and colonisation. The beekeeper-figure appears as a kind of colonising agent, master of his trade, tirelessly ‘reigning in the bee’.2 ; ; Or is it more harmless than this? Swathed in his unwieldy suit, the caretaker’s identity remains out of reach, the character protected from our curious gaze. Like so much in Bush’s paintings, the suit is a kind of barrier preventing the viewer from perceiving what is really going on in the narrative. We wonder who the caretaker is tending to; what he is responsible for. He appears time and time again in these paintings, patiently toiling away at his repetitive discipline beneath the phosphorescent sky. Perhaps the caretaker can be read as a more affirmative figure, a guardian of sorts. Maybe his secret business is the protection of endangered civilisations – of the human world, and the fragile state it has found itself in post-colonisation. ; ; The caretaker may also be a substitute for the artist himself. Up to this point, Stephen Bush has appeared in the majority of his works as one of his characters; in drag, in uniform, in colonial outfits, driving tractors or chopping down trees. The Caretaker paintings are among the first images in which the artist as a character disappears. One has to assume that it is the artist hidden within the caretaker’s suit. The protective clothing may be but a reminder of the potential peril of his chosen career, protecting himself from the dangers and the terror of his work. ; ; It is also worth noting that although similar in content, the styles in which the four caretaker works are painted are quite different. In fact, these four painting were each depicted with their own deliberate referential style. The Caretaker (lot 73) draws upon the Hudson River School, and in particular Frederick Church who was instrumental in defining the aesthetic romanticism of the American Landscape. A Caretaker (2) (lot 74) alludes to the Rocky Mountain School, a group of artists in America’s Wild West inspired to paint large scenes of the Rocky Mountains with an emphasis on dramatic effect. A Caretaker (3) (lot 75) is painted in homage to the Pre-Raphaelites who painted with an accuracy that mimicked photography. Finally, A Caretaker (4) (lot 76) recalls the Nazarene movement adopted by German painters in the early 19th Century who aimed to revive a more spiritual element in their work. The Caretaker series pays very specific tribute to these movements which Bush saw as the predominant schools of landscape painting in the 19th Century and who contributed significantly to the way the public viewed the natural landscape. ; ; 1. Natasha Bullock, ‘When I was here, I wanted to be there’, Art and Australia, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2011 ; 2. Ashley Crawford, ‘Metaphor, Melancholia and Mayhem’ in Stephen Bush: Gelderland, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2007 exhibition catalogue ; ; LEAH CROSSMAN

-

Estimate:A$30,000 - 40,000

-

Realised Price:

-

Category:Art

This Sale has been held and this item is no longer available. Details are provided for information purposes only.